The acronym ADPKD stands for Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. The name

refers to one of two types of genetically-

Cause

ADPKD is a genetic disease caused by a hereditary abnormality in the genes. As the name implies, the gene is an autosomal dominant which can appear in offspring of either parent without the other parent also being a carrier of the gene. There are three separate genetic abnormalities that manifest in the same phenotypal expression and result in the disease. Most of the cases of ADPKD (85%) are the result of a genetic abnormality on Chromosome 16 that carries code for a protein involved in transport of calcium. As is typical for dominant genetic diseases, most of the cases of ADPKD appear in families that have a history of the disease.

Symptoms

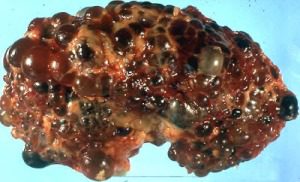

Symptoms of the disease can appear in gestation. Cysts form in the kidneys, accumulate fluid, and become enlarged. As they grow, the cysts separate from the kidney vessels where they form and begin to interfere with kidney function. Over time and the development of multiple cysts, usually in both kidneys, the kidneys themselves become visibly enlarged and kidney function becomes significantly impaired. The cysts may begin to form at any time in life, and the disease’s overt manifestation is more common in adults than in childhood.

In addition to the cysts in the kidneys which are the primary manifestation, the disease can also produce cysts in other parts of the body, including the liver, pancreas and testes. The condition can produce aortic aneurysms, brain aneurysms, diverticula of the colon, abdominal pain, blood in the urine, excessive nighttime urination, joint pain, drowsiness, and abnormality of the nails. The disease progresses quite slowly, but eventually can lead to severe, end-

Diagnosis

There are a number of blood and urine tests that can indicate the presence of this abnormality, including a complete blood count. Cerebral angiography can be done in the case of frequent headaches to determine whether they are associated with brain aneurysms. Medical imaging can be used to visually discover the presence of cysts in the kidneys. Finally, genetic testing can be done to determine the presence of the culprit genes. This last is recommended in cases of family history of PKD.

Treatment

At present, the goal of treatment of PKD is to control symptoms and prevent complications. Keeping blood pressure down is important, although it is also more difficult than with more common forms of high blood pressure. Medications, a low-

The number of cysts that form make it impractical to remove or drain all of them. However, in cases where a cyst becomes painful or results in urinary blockage, it may be necessary to surgically drain it.

Since the progression of the disease is slow, symptomatic treatment may suffice to control the disease for many years. Progression to the late

stage of the condition may require replacement renal therapy. This can include dialysis to replace kidney function, or a kidney transplant. Patients with PKD are often good candidates for a transplant, although cysts can form in the transplant kidney as well; however, effectively the disease “starts all over” in that case.

Research

At present, there is no way to prevent cysts from forming and enlarging in patients with genetic PKD. However, some research has been done in which rats with the condition was found to reverse itself to a significant degree when they were treated with drugs that inhibited the production of vasopressin, a chemical that may be involved in the formation of cysts. The research suggests that drinking large amounts of water may have the same effect in the early stages of the disease, since water intake also suppresses vasopressin. However, it is not yet known whether the same treatments will be effective in humans. Clinical trials are still under way.

In the long run, it may be that genetic disorders such as this may possibly be treated by recombinant genetic therapy to correct the defective genes themselves. However, such methods are much further from implementation than any therapy that is currently available or in clinical trials.